The two of us would go with our mom to the fabric store on summer days, when we all needed to get out of the house. That’s how she phrased it, let’s get out of the house. And she called it Hancock’s, made it possessive, even though it wasn’t, and dropped the “Fabric” part altogether, as though they were on a first-name basis. Sometimes she actually needed fabric, or a pattern, or notions;I loved that section, zippers and pincushions and piping; I told her that once, saying I liked the notion of notions, and she was amazed at my cleverness. I didn’t have the heart to tell her I’d heard it somewhere else: Mrs. Harless, down the street.

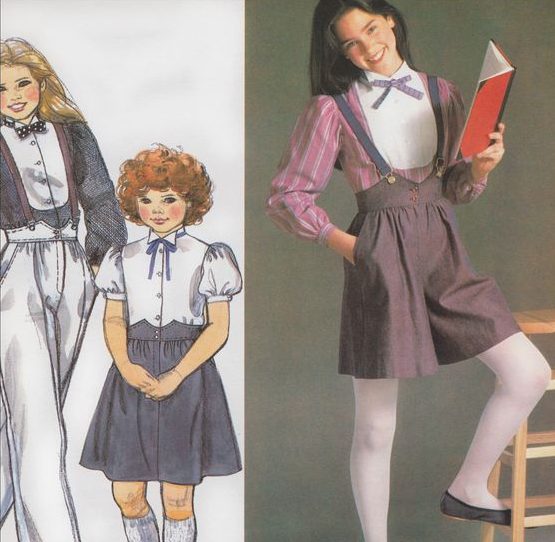

She would shop and my sister and I would look at patterns: our favorite was Simplicity and Butterick Girls, their main girl-model was so pretty. That girl would get straight A’s, you could tell, and sleep in a pink canopy bed with a cocker spaniel in a basket on the floor.

You’d look good in this one, we’d say, or I want a skirt like that but blue, or we’d find the pictures of boys in homemade sailor suits and laugh at them, see if there were any cute ones. We could look at buttons for ages without getting bored, picking out our favorites, reds and yellows and blues and all shades of brown spilling over the sides of the bin and making the loveliest sound when you lay your hand flat and swished it back and forth, or dug both hands in deep and pulled up fist-fulls, letting the buttons pour back into the button ocean. Unattainable, unless we’d saved allowance.

She, my mother, bit her lip a little, in concentration, scrutinizing the isles of calico or chintz or damask or seersucker, big purse under her arm, big sunglasses on her head, pulling back short blond hair, gold stud earrings from Tiffany’s in her ears, the only ones she ever wore and only thing she ever owned from Tiffanys, and I would think: she is beautiful, she is beautiful, and I am lucky, I am lucky and my chest would hurt a little, I remember that, from the happiness of it.

My sister was bored, I knew, and growing weary of handmade clothes, but I was younger and wanted to stay forever.

Once, when we got home, the gross boy next door asked where we’d been and when we told him Hancock Fabric, he laughed his nasal laugh, making a gesture with his hand that made no sense, saying Get it? Hand-cock? Get it? I did not but my sister’s face pinched up and she shoved him into the gravel on the sides of his driveway and his mother came out and yelled at her, saying she was older so she was a bully, which temporarily ruined Hancock Fabric for me, but I see now that she was trying to save it.